Embedding Python in Go

Python can get embedded as a shared library into programs written in other languages. Here’s a trivial example for executing Python code in a Golang program and exchanging data between the two runtimes.

A couple of days ago Miki Tebeka posted an interesting article on the Ardan Labs blog that explores a way of calling Python code from Golang code in memory.

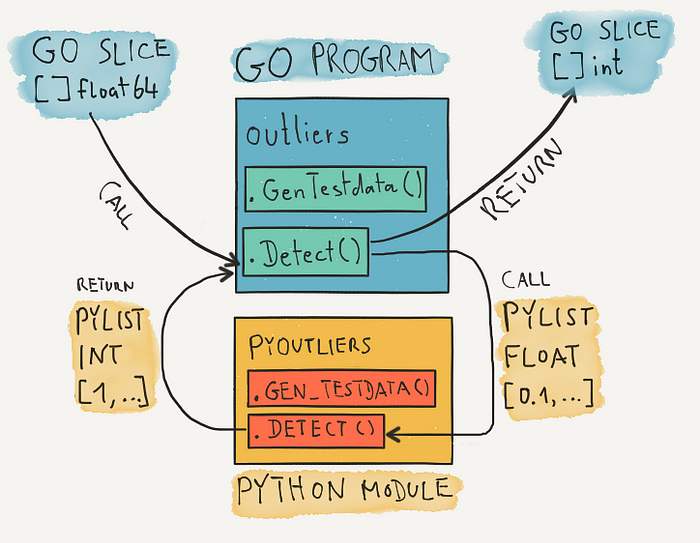

In short the article describes this example: There’s a Python function detect() that takes as input a Python list of float values and uses a numpy oneliner to detect which of these values are an anomaly* in the dataset. It returns the list indices of the identified values as a new Python list of integers. The goal is to call this function from Go with passing input and return data between the Go and Python runtimes.

(* here: values that are more than 2 standard deviations from mean)

This is a really good example usecase where using Python code in a Go program can be useful: We want to use a “high value” Python library (here: numpy) that provides easy access to complex functionality that wouldn’t be necessarily trivial to implement in Go.

The solution that the Ardan Labs blog post describes is highly optimized for performance and low memory consumption. It’s quite impressive in that regard. After the function call the program only holds the Go objects in memory. It achieves this by using some carefully crafted C glue code to share memory between Python and Go.

In this blogpost I’d like to try to achieve the same functionality, but take a different road: We’re only going to use high level interfaces directly from Go — namely the Python C API. It makes things a bit simpler and more approachable, at a performance cost.

This means we will let Python and Go manage their memory allocations separately and will, where needed, copy data between the two runtimes. This, of course, comes at a performance and memory consumption price (at some point data exists twice in memory).

So what’s the benefit? Well, it’s usually simpler and more approachable to write and maintain high level code. We don’t need to dive into low level arts to achieve the desired functionality but instead can work with a well documented API. We don’t need to write C code. But we still can call Python in memory from Go (as a shared library), which is relatively fast. So compared to the shared memory solution from the Ardan Labs blogpost I’d argue it’s a tradeoff for more approachability at the cost of reduced efficiency.

Let’s dive in. I’m not going over all of the code, it’s here in full on GitHub.

1. Our example at a high level

The Python side

We have a Python module called pyoutliers that provides a function that with type hints looks like:

def detect(data: list[float]) -> list[int]:

# ...It takes a list of float values, does its numpy magic and returns a list of integer values.

To make it easy to test this function we also have a little helper function gen_testdata() to generate some input testdata. It returns a list of 1k random float values. The values at indices 7, 113 and 835 are always exceptionally high.

In a Python3 shell we could run (and would always get the same result):

>>> from pyoutliers import detect, gen_testdata

>>> print(detect(gen_testdata()))

[7, 113, 835]The Go side

Our goal is to have wrapper functions in Go for these two Python functions that take and return Go objects.

2. Using the Python C API in Go

Python can be dynamically linked to as a shared library (.dll / .lib.so).

Prerequisites

Prerequisite is a Python3 installation (for this example preferably Python 3.7) with the header files (on most Linux distros provided by the python3-devel package). We’ll also use the pkg-config tool, which can get installed as package pkgconfig by package managers (on Windows try choco install pkgconfiglite).

For our full example later we’ll also need numpy as a dependency of our pyoutliers Python module: pip3 install numpy.

The Python(-devel) installation should provide a pkg-config file for Python. It tells the compiler where to find the library and header files. Its location is different with every OS, here are some examples (but it might be somewhere else on your system):

- Fedora 32:

/lib64/pkgconfig/python3-embed.pc - MacOS (via Python 3.7 installer from python.org):

/Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/3.7/lib/pkgconfig/python-3.7.pc - on Windows you might have to create it yourself, here’s an example

A simple example

1 package main

2

3 // #cgo pkg-config: python3

4 // #include <Python.h>

5 import "C"

6

7 import (

8 "unsafe"

9 )

10

11 func main() {

12

13 pycodeGo := `

14 import sys

15 for path in sys.path:

16 print(path)

17 `

18

19 defer C.Py_Finalize()

20 C.Py_Initialize()

21 pycodeC := C.CString(pycodeGo)

22 defer C.free(unsafe.Pointer(pycodeC))

23 C.PyRun_SimpleString(pycodeC)

24

25 }We can go build it by setting the path to the dir with the python3.pc file (if it’s named differently on our system we can symlink it):

export PKG_CONFIG_PATH=/some-dir/pkg-config/

go buildLine 3 defines the name of the .pc file to be used. Line 4 includes Python. Both only work in combination with the import of the C package in line 5. In line 13 we create a multi line string Go variable in which we store some Python code (here: a loop that prints all members of Python’s sys.path). Lines 19 and 20: Before we can call any other function from the Python C API we first need to initialize the Python interpreter (and make sure that it gets finalized before the program exits through a defer). In line 23 we make the call against the Python C API function that triggers the execution of the code from our string. It’s defined as int PyRun_SimpleString(const char *command) — which means it wants a C_char as input, which we create in line 21. The char is out of scope of Go’s memory management, so we need to free() it manually once it isn’t needed anymore, which we can do conveniently with a defer in line 22.

(Note: All error handling is left out from the example to keep it simple).

Making it more Go-like

That’s basically how interacting with the Python C API works. Unlike the very basic function that we’ve just called most functions take and/or return objects of the PyObject type. No matter if we have a Python string, module or list — it’s always a PyObject.

To make things more Go-like we could now start to define Go types and functions like:

type PyObject C.PyObjector

func PyRun_SimpleString(command string) int {

commandC := C.CString(command)

defer C.free(unsafe.Pointer(commandC))

return int(C.PyRun_SimpleString(commandC))

}Luckily the fine folks from Datadog have already done that for almost the entire Python3 C API in a very handy Go module called go-python3.

Meet go-python3: Python bindings for go

Here’s a similar example using go-python3 :

1 package main

2

3 import "github.com/DataDog/go-python3"

4

5 func main() {

6

7 defer python3.Py_Finalize()

8 python3.Py_Initialize()

9 python3.PyRun_SimpleString("print('hello world')")

10

11 }Note that we can now directly use a Go string in the call to PyRun_SimpleString. That’s very nice, isn’t it?

In order to be able to go build this example we need exactly Python 3.7 (for a Python 3.8 workaround see the note at the end of this article) and the pkg-config file in the dir that PKG_CONFIG_PATH points to needs to be exactly named python3.pc.

Memory management

Both Go and Python manage memory automatically. However, when using PyObjects in Go we need to manually help the Python runtime to understand if an object is still needed. Every PyObject has a reference count and if it drops to 0 Python’s garbage collector knows it can free the memory. Sometimes we need to decrement the refcount when we don’t need an object anymore and sometimes we need to increment it to ensure that the memory doesn’t get free’ed too soon.

Each python3.PyObject has a .DecRef() and a .IncRef() method for that.

So what and when? When we call a Python C API function these three defined things can happen for input and returned PyObjects: (The docs for each function tell us precisely what the behaviour is)

Return value: “New” reference

The reference count for the returned PyObject has already been incremented for us.

- Where: Mostly functions that create new objects (i.e.

PyList_New) - What to do: Either you decref the PyObject once you don’t need it anymore or give it to someone who will (i.e. another function that “steals” it or pass it as return value to a caller that decrefs it). Otherwise you have a memory leak.

The function “steals” a reference to an item

- Where: Mostly functions that set items (i.e.

PyList_SetItem) - What to do: Nothing. The thief will take care of things so you don’t have to. If you try to decref the object directly the results are undefined.

Return value: “Borrowed” reference

Two pointers to the same memory location

- Where: Mostly functions that get items (i.e.

PyList_GetItem) - What to do: If you want to continue to work with that object/pointer increment the reference count (and take care that it later gets decref’ed somehow).

One word of debugging advice: Looking up an object’s reference count isn’t necessarily super useful. Not only because looking it up can increase it but also because of Python’s internal optimizations. The refcount might be different than what you expect. Instead the docs are your best friend. The manual tells you exactly what the expected behaviour is for every Python C API function.

3. Creating our “outliers” program in Go

Project structure

Our go program will be called outliers and the project folder looks like this:

└── outliers

├── go.mod

├── main.go

├── pkg-config

│ └── python3.pc

└── pyoutliers

├── __init__.py

└── detect.pyThe pyoutliers dir is our Python module. It exposes the Python functions gen_testdata() and detect(). Our Go program expects to find the Python module in the same path — which is the case if we build into the same dir via PKG_CONFIG_PATH=./pkg-config go build.

All of our Go code is in main.go. It contains the following main functions:

main()contains the parts that are either not repeatable or don’t make sense to repeat in terms of this example. That’s mainly initializing Python and importingnumpy. (Numpy relies on a C extension and isn’t easily “reloadable” in memory — that’s why we can’t repeat the Python initialization and finalization. More about that later). After these preparations this function callsdemo().demo()performs a complete demo run of our functionality: It callsgenTestdata()to get a Go slice with test data. It then callsdetect()with the test data. This function can get called repeatedly (i.e. we could have a loop inmain()that callsdemo()).

Then we have Go functions that wrap around the corresponding Python functions:

genTestdata()is a Go wrapper function around the Python functiongen_testdata()and returns a Go slice[]float64.detect()is the Go wrapper function around the Python functiondetect(). It takes a[]float64slice and returns an[]intslice.

And in addition we have a little utility function:

goSliceFromPylist()takes a PyObject that points to a Python montype list and returns a Go slice. It’s being used by bothdetect()andgenTestdata().

Python Initialization and Import of our Python module

In main() we initialize Python as usual

defer python3.Py_Finalize()

python3.Py_Initialize()We then determine the path to the executable itself and add it to Python’s package search path by executing some trivial Python code with PyRun_SimpleString.

dir, err := filepath.Abs(filepath.Dir(os.Args[0]))

//...

ret := python3.PyRun_SimpleString("import sys\nsys.path.append(\"" + dir + "\")")We can then import and add the pyoutliers module:

oImport := python3.PyImport_ImportModule("pyoutliers") //ret val: new ref

//...

defer oImport.DecRef()

oModule := python3.PyImport_AddModule("pyoutliers") //ret val: borrowed ref (from oImport)As to the docs PyImport_ImportModule returns a PyObject with a new reference. This means we need to decrement the reference count of the object once we don’t need it anymore. We can make sure of that by deferring a call to this <python3.PyObject>’s .DecRef() function.

It’s a bit different for our call to PyImport_AddModule(). We pass the PyObject that we’ve received from the previous function call to it as argument. The docs tell us that PyImport_AddModule() won’t return a new reference but borrows the reference of the input. So we don’t need to decref the return value.

Now we can call demo() and pass the pyoutliers module PyObject as argument.

demo(oModule)The demo function is very simple: It just calls our two wrapper functions (again each with the pyoutliers PyObject as argument):

func demo(module *python3.PyObject) { testdata, err := genTestdata(module)

//...

outliers, err := detect(module, testdata)

//...

fmt.Println(outliers)}

Calling a Python function from Go

In both of our wrapper functions we try to find the Python function that we want to call. Python heavily works with dictionaries (in fact all “root” objects in Python are members of the __main__ dict). In our case we need to get the dict of the pyoutliers module. In the genTestdata() function:

oDict := python3.PyModule_GetDict(module)and there we can find its attributes and methods — including the gen_testdata() function.

genTestdata := python3.PyDict_GetItemString(oDict, "gen_testdata")We can now test if it’s actually a function and if so call it:

genTestdata := python3.PyDict_GetItemString(oDict, "gen_testdata")

if !(genTestdata != nil && python3.PyCallable_Check(genTestdata)) {

// raise error

}

testdataPy := genTestdata.CallObject(nil) //retval: New reference

//...

defer testdataPy.DecRef()In this case we have now received a new PyObject (a PyList) with a new reference to it that we need to decref once we don’t need it anymore. (We can then pass it to the goSliceFromPylist helper function to convert it to a Go slice before returning it — more on that later).

Passing data as argument to a Python function

Things work the same way for our other wrapper function, detect(), the only major difference is that here we create and pass a PyObject as argument to the Python detect() function. Let’s have a look:

We’re holding a Go []float64 slice called data. We need to copy its members to a Python list.

(Side note: Here we’re hitting the major difference — and also disadvantage — compared to the Ardan Labs blog solution: We don’t let Go and Python access the same memory location. Instead we’re copying data from Go to Python by calling high level functions).

First we need to create a new PyList:

pylist := python3.PyList_New(len(data)) //retval: New reference, gets stolen laterThen we can iterate over the Go slice’s members and add them to the PyList:

for i := 0; i < len(data); i++ {

item := python3.PyFloat_FromDouble(data[i]) //ret val: New reference, gets stolen later

ret := python3.PyList_SetItem(pylist, i, item)

if ret != 0 {

if python3.PyErr_Occurred() != nil {

python3.PyErr_Print()

}

item.DecRef()

pylist.DecRef()

return nil, fmt.Errorf("error setting list item")

}

}For every item in the Go slice we’re first creating a new PyFloat PyObject. It’s a new reference. However, we don’t need to decref it — because we’re going to add it to a PyList by passing it to PyList_SetItem(). This function call, according to the docs, steals the PyFloat’s reference. By doing so it becomes owned by the PyList. In other words: When we decref the PyList object, all of its members will get automatically decref’ed.

Now we have a Python list that contains a copy of each of the float values from the Go slice.

We intend to use it as argument for calling the pyoutliers.detect() Python function, which we already hold as Go object detect, so we can call detect.CallObject(args)

Arguments for Python function calls need to be wrapped into a PyTuple first — this works the same way as creating and “filling” a PyList (using PyTuple_New and PyTuple_SetItem).

Iterating over a Python list from Go

Both of our wrapper functions call our helper function goSliceFromPylist(). It takes a PyList and coverts it to a Go slice. I’m not going over it in detail but would like to highlight one concept that we haven’t discussed yet: Iterating over a PyObject, like a PyList.

Here, we’re having a PyList PyObject pylist that we want to iterate over. First we need to create an iterator:

seq := pylist.GetIter() //ret val: New reference

//...

defer seq.DecRef()The iterator has a method __next__() that returns the next item (or nil if there are no items left):

tNext := seq.GetAttrString("__next__") //ret val: new ref

//...

defer tNext.DecRef()We can call it for the number of items in the list:

pylistLen := pylist.Length()for i := 1; i <= pylistLen; i++ {

item := tNext.CallObject(nil) //ret val: new ref

// do something

if item != nil {

item.DecRef()

}

Let’s build & run our program!

PKG_CONFIG_PATH=./pkg-config go build

./outliers

[7 113 835]Yippee! 🎉🥳 A numpy calculation result in Go!

3. Bonus section: One more thing… (actually three)

We’ve reached the end of this blog post. If you’re still not tired to read on, here’s some bonus stuff.

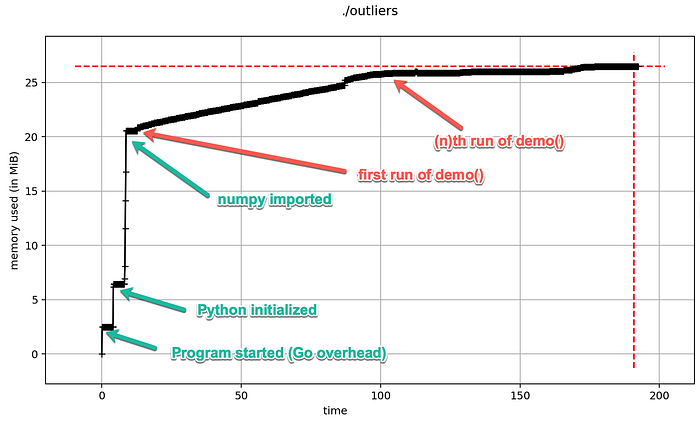

Bonus #1: Do we have a leak? (TL;DR: No, it’s just Go)

In our main function we call demo() once. Let’s change it to an endless loop and run it for a while.

for {

demo(oModule)

}Each run should consume roughly the same amount of memory and therefore we should see pretty constant memory usage, Right?

Well … when we run the program now we can see something else happen: With every cycle the memory usage increases — until it stagnates after a number of cycles.

What’s happening? Why is the memory usage increasing? Do we have a memory leak? Did we forget to decref a PyObject?

No, it’s just Go’s automatic and opinionated memory management (after all Go is optimized for server apps).

Go is very attached to memory that it allocates, meaning that it holds on to it for a while before releasing the memory to the operating system. If your service has a peak in memory consumption and has at least 5 minutes of “calmness”, Go will start releasing memory to the operating system. Before that, it will hold on to it in case it needs that memory again to avoid the overhead of asking the operating system to reallocate more memory. (source)

If we add a sleep of 6 minutes after a number of demo() runs we see the memory usage magically drop down to levels similar to the first run of demo().

Alternatively we could — for debugging — force a more aggressive release of memory between every run of demo() by triggering a garbage collection and the release of memory to the OS in our loop:

for {

demo(oModule)

runtime.GC()

debug.FreeOSMemory()}

So, no leak — just the expected behaviour of Go.

Bonus #2: Why can’t we loop over the entire code? (TL;DR: numpy isn’t reloadable)

Python itself is restartable in memory. So we could run the Python initialization and finalization (and arbitrary Python code in between) in a loop:

for {

python3.Py_Initialize()

python3.PyRun_SimpleString("print('hello')")

python3.Py_Finalize()}

However some Python C extensions are not reloadable. Numpy is one of them. Trying to load numpy a second time after a Py_Finalize() will lead to a segfault:

python3.Py_Initialize()

python3.PyRun_SimpleString("import numpy")

python3.Py_Finalize()

python3.Py_Initialize()

python3.PyRun_SimpleString("import numpy")

// segfault happening hereThis shouldn’t stop us from using numpy in Go. It’s just the same as when loading numpy in a standalone Python process — you can’t really get it out of memory once loaded.

Bonus #3: How to use “go-python3” with Python 3.8+

go-python3

Currently supports python-3.7 only

(from the go-python3 README).

I had success running go-python3 with Python 3.8 on Win, Mac, Linux after having removed the binding for the PyEval_ReInitThreads function, which has been removed from the Python C API starting with Python 3.8. I haven’t tested with Python 3.9 yet.

4. Wrapping up

Again, the full source code for this example is on github. Feel free to submit PRs for improvements or leave comments here for questions and feedback.

More resources

If you’re interested to explore more ways of interacting between Python and Go (like writing Python extensions in Go or passing data between Python and Go using grpc) I can highly recommend Miki Tebeka’s four part article series on the Ardan Labs blog. It inspired me to write this blog post. (Update Feb 2021: Miki Tebeka also held a talk on the topic at Fosdem’21).

For an extended dive into the concepts of the Python C API (and memory management in particular) I find Paul Ross’ Coding Patterns for Python Extensions very resourceful.

If you need to hold on to Python 2 there’s a similar Go package like go-python3 for Py2 called sbinet/go-python.

There’s also a #go-python channel on Gophers Slack.

And finally there’s a new book CPython Internals in the works by Anthony Shaw. So far I’ve only read some bits and pieces in the early edition, but it looks like a great resource.