Watch Now This tutorial has a related video course created by the Real Python team. Watch it together with the written tutorial to deepen your understanding: Exploring Keywords in Python

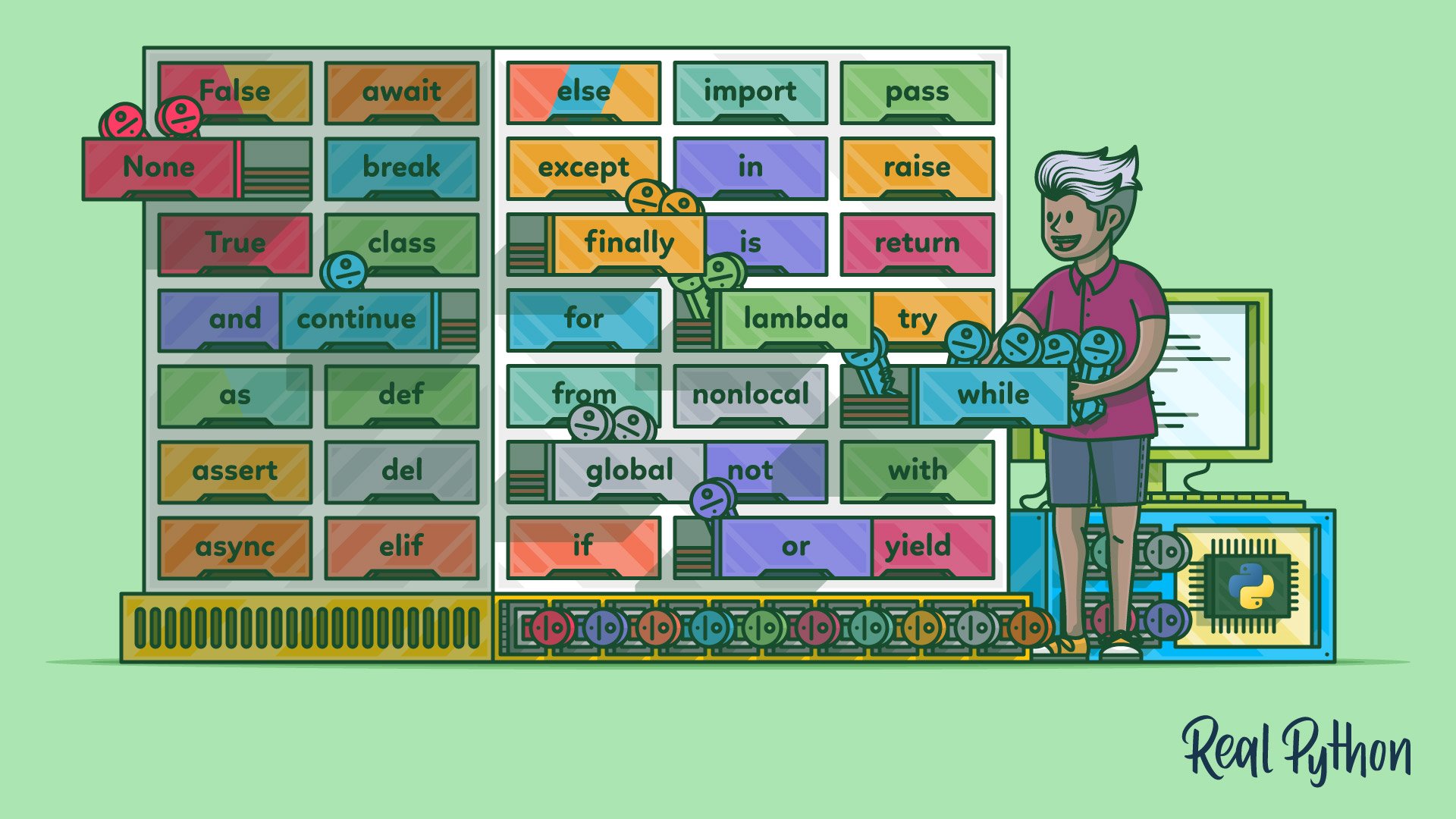

Every programming language has special reserved words, or keywords, that have specific meanings and restrictions around how they should be used. Python is no different. Python keywords are the fundamental building blocks of any Python program.

In this article, you’ll find a basic introduction to all Python keywords along with other resources that will be helpful for learning more about each keyword.

By the end of this article, you’ll be able to:

- Identify Python keywords

- Understand what each keyword is used for

- Work with keywords programmatically using the

keywordmodule

Free Bonus: 5 Thoughts On Python Mastery, a free course for Python developers that shows you the roadmap and the mindset you’ll need to take your Python skills to the next level.

Python Keywords

Python keywords are special reserved words that have specific meanings and purposes and can’t be used for anything but those specific purposes. These keywords are always available—you’ll never have to import them into your code.

Python keywords are different from Python’s built-in functions and types. The built-in functions and types are also always available, but they aren’t as restrictive as the keywords in their usage.

An example of something you can’t do with Python keywords is assign something to them. If you try, then you’ll get a SyntaxError. You won’t get a SyntaxError if you try to assign something to a built-in function or type, but it still isn’t a good idea. For a more in-depth explanation of ways keywords can be misused, check out Invalid Syntax in Python: Common Reasons for SyntaxError.

As of Python 3.8, there are thirty-five keywords in Python. Here they are with links to the relevant sections throughout the rest of this article:

False |

await |

else |

import |

pass |

None |

break |

except |

in |

raise |

True |

class |

finally |

is |

return |

and |

continue |

for |

lambda |

try |

as |

def |

from |

nonlocal |

while |

assert |

del |

global |

not |

with |

async |

elif |

if |

or |

yield |

You can use these links to jump to the keywords you’d like to read about, or you can continue reading for a guided tour.

Note: Two keywords have additional uses beyond their initial use cases. The else keyword is also used with loops as well as with try and except. The as keyword is also used with the with keyword.

How to Identify Python Keywords

The list of Python keywords has changed over time. For example, the await and async keywords weren’t added until Python 3.7. Also, both print and exec were keywords in Python 2.7 but have been turned into built-in functions in Python 3+ and no longer appear in the list of keywords.

In the sections below, you’ll learn several ways to know or find out which words are keywords in Python.

Use an IDE With Syntax Highlighting

There are a lot of good Python IDEs out there. All of them will highlight keywords to differentiate them from other words in your code. This will help you quickly identify Python keywords while you’re programming so you don’t use them incorrectly.

Use Code in a REPL to Check Keywords

In the Python REPL, there are a number of ways you can identify valid Python keywords and learn more about them.

Note: Code examples in this article use Python 3.8 unless otherwise indicated.

You can get a list of available keywords by using help():

>>> help("keywords")

Here is a list of the Python keywords. Enter any keyword to get more help.

False class from or

None continue global pass

True def if raise

and del import return

as elif in try

assert else is while

async except lambda with

await finally nonlocal yield

break for not

Next, as indicated in the output above, you can use help() again by passing in the specific keyword that you need more information about. You can do this, for example, with the pass keyword:

>>> help("pass")

The "pass" statement

********************

pass_stmt ::= "pass"

"pass" is a null operation — when it is executed, nothing happens. It

is useful as a placeholder when a statement is required syntactically,

but no code needs to be executed, for example:

def f(arg): pass # a function that does nothing (yet)

class C: pass # a class with no methods (yet)

Python also provides a keyword module for working with Python keywords in a programmatic way. The keyword module in Python provides two helpful members for dealing with keywords:

kwlistprovides a list of all the Python keywords for the version of Python you’re running.iskeyword()provides a handy way to determine if a string is also a keyword.

To get a list of all the keywords in the version of Python you’re running, and to quickly determine how many keywords are defined, use keyword.kwlist:

>>> import keyword

>>> keyword.kwlist

['False', 'None', 'True', 'and', 'as', 'assert', 'async', ...

>>> len(keyword.kwlist)

35

If you need to know more about a keyword or need to work with keywords in a programmatic way, then Python provides this documentation and tooling for you.

Look for a SyntaxError

Finally, another indicator that a word you’re using is actually a keyword is if you get a SyntaxError while trying to assign to it, name a function with it, or do something else that isn’t allowed with it. This one is a little harder to spot, but it’s a way that Python will let you know you’re using a keyword incorrectly.

Python Keywords and Their Usage

The sections below organize the Python keywords into groups based on their usage. For example, the first group is all the keywords that are used as values, and the second group is the keywords that are used as operators. These groupings will help you better understand how keywords are used and provide a nice way to organize the long list of Python keywords.

There are a few terms used in the sections below that may be new to you. They’re defined here, and you should be aware of their meaning before proceeding:

-

Truthiness refers to the Boolean evaluation of a value. The truthiness of a value indicates whether the value is truthy or falsy.

-

Truthy means any value that evaluates to true in the Boolean context. To determine if a value is truthy, pass it as the argument to

bool(). If it returnsTrue, then the value is truthy. Examples of truthy values are non-empty strings, any numbers that aren’t0, non-empty lists, and many more. -

Falsy means any value that evaluates to false in the Boolean context. To determine if a value is falsy, pass it as the argument to

bool(). If it returnsFalse, then the value is falsy. Examples of falsy values are"",0,[],{}, andset().

For more on these terms and concepts, check out Operators and Expressions in Python.

Value Keywords: True, False, None

There are three Python keywords that are used as values. These values are singleton values that can be used over and over again and always reference the exact same object. You’ll most likely see and use these values a lot.

The True and False Keywords

The True keyword is used as the Boolean true value in Python code. The Python keyword False is similar to the True keyword, but with the opposite Boolean value of false. In other programming languages, you’ll see these keywords written in lowercase (true and false), but in Python they are always written in uppercase.

The Python keywords True and False can be assigned to variables and compared to directly:

>>> x = True

>>> x is True

True

>>> y = False

>>> y is False

True

Most values in Python will evaluate to True when passed to bool(). There are only a few values in Python that will evaluate to False when passed to bool(): 0, "", [], and {} to name a few. Passing a value to bool() indicates the value’s truthiness, or the equivalent Boolean value. You can compare a value’s truthiness to True or False by passing the value to bool():

>>> x = "this is a truthy value"

>>> x is True

False

>>> bool(x) is True

True

>>> y = "" # This is falsy

>>> y is False

False

>>> bool(y) is False

True

Notice that comparing a truthy value directly to True or False using is doesn’t work. You should directly compare a value to True or False only if you want to know whether it is actually the values True or False.

When writing conditional statements that are based on the truthiness of a value, you should not compare directly to True or False. You can rely on Python to do the truthiness check in conditionals for you:

>>> x = "this is a truthy value"

>>> if x is True: # Don't do this

... print("x is True")

...

>>> if x: # Do this

... print("x is truthy")

...

x is truthy

In Python, you generally don’t need to convert values to be explicitly True or False. Python will implicitly determine the truthiness of the value for you.

The None Keyword

The Python keyword None represents no value. In other programming languages, None is represented as null, nil, none, undef, or undefined.

None is also the default value returned by a function if it doesn’t have a return statement:

>>> def func():

... print("hello")

...

>>> x = func()

hello

>>> print(x)

None

To go more in depth on this very important and useful Python keyword, check out Null in Python: Understanding Python’s NoneType Object.

Operator Keywords: and, or, not, in, is

Several Python keywords are used as operators. In other programming languages, these operators use symbols like &, |, and !. The Python operators for these are all keywords:

| Math Operator | Other Languages | Python Keyword |

|---|---|---|

| AND, ∧ | && |

and |

| OR, ∨ | || |

or |

| NOT, ¬ | ! |

not |

| CONTAINS, ∈ | in |

|

| IDENTITY | === |

is |

Python code was designed for readability. That’s why many of the operators that use symbols in other programming languages are keywords in Python.

The and Keyword

The Python keyword and is used to determine if both the left and right operands are truthy or falsy. If both operands are truthy, then the result will be truthy. If one is falsy, then the result will be falsy:

<expr1> and <expr2>

Note that the results of an and statement will not necessarily be True or False. This is because of the quirky behavior of and. Rather than evaluating the operands to their Boolean values, and simply returns <expr1> if it is falsy or else it returns <expr2>. The results of an and statement could be passed to bool() to get the explicit True or False value, or they could be used in a conditional if statement.

If you wanted to define an expression that did the same thing as an and expression, but without using the and keyword, then you could use the Python ternary operator:

left if not left else right

The above statement will produce the same result as left and right.

Because and returns the first operand if it’s falsy and otherwise returns the last operand, you can also use and in an assignment:

x = y and z

If y is falsy, then this would result in x being assigned the value of y. Otherwise, x would be assigned the value of z. However, this makes for confusing code. A more verbose and clear alternative would be:

x = y if not y else z

This code is longer, but it more clearly indicates what you’re trying to accomplish.

The or Keyword

Python’s or keyword is used to determine if at least one of the operands is truthy. An or statement returns the first operand if it is truthy and otherwise returns the second operand:

<expr1> or <expr2>

Just like the and keyword, or doesn’t convert its operands to their Boolean values. Instead, it relies on their truthiness to determine the results.

If you wanted to write something like an or expression without the use of or, then you could do so with a ternary expression:

left if left else right

This expression will produce the same result as left or right. To take advantage of this behavior, you’ll also sometimes see or used in assignments. This is generally discouraged in favor of a more explicit assignment.

For a more in-depth look at or, you can read about how to use the Python or operator.

The not Keyword

Python’s not keyword is used to get the opposite Boolean value of a variable:

>>> val = "" # Truthiness value is `False`

>>> not val

True

>>> val = 5 # Truthiness value is `True`

>>> not val

False

The not keyword is used in conditional statements or other Boolean expressions to flip the Boolean meaning or result. Unlike and and or, not will determine the explicit Boolean value, True or False, and then return the opposite.

If you wanted to get the same behavior without using not, then you could do so with the following ternary expression:

True if bool(<expr>) is False else False

This statement would return the same result as not <expr>.

The in Keyword

Python’s in keyword is a powerful containment check, or membership operator. Given an element to find and a container or sequence to search, in will return True or False indicating whether the element was found in the container:

<element> in <container>

A good example of using the in keyword is checking for a specific letter in a string:

>>> name = "Chad"

>>> "c" in name

False

>>> "C" in name

True

The in keyword works with all types of containers: lists, dicts, sets, strings, and anything else that defines __contains__() or can be iterated over.

The is Keyword

Python’s is keyword is an identity check. This is different from the == operator, which checks for equality. Sometimes two things can be considered equal but not be the exact same object in memory. The is keyword determines whether two objects are exactly the same object:

<obj1> is <obj2>

This will return True if <obj1> is the exact same object in memory as <obj2>, or else it will return False.

Most of the time you’ll see is used to check if an object is None. Since None is a singleton, only one instance of None that can exist, so all None values are the exact same object in memory.

If these concepts are new to you, then you can get a more in-depth explanation by checking out Python ‘!=’ Is Not ‘is not’: Comparing Objects in Python. For a deeper dive into how is works, check out Operators and Expressions in Python.

Control Flow Keywords: if, elif, else

Three Python keywords are used for control flow: if, elif, and else. These Python keywords allow you to use conditional logic and execute code given certain conditions. These keywords are very common—they’ll be used in almost every program you see or write in Python.

The if Keyword

The if keyword is used to start a conditional statement. An if statement allows you to write a block of code that gets executed only if the expression after if is truthy.

The syntax for an if statement starts with the keyword if at the beginning of the line, followed by a valid expression that will be evaluated for its truthiness value:

if <expr>:

<statements>

The if statement is a crucial component of most programs. For more information about the if statement, check out Conditional Statements in Python.

Another use of the if keyword is as part of Python’s ternary operator:

<var> = <expr1> if <expr2> else <expr3>

This is a one-line version of the if...else statement below:

if <expr2>:

<var> = <expr1>

else:

<var> = <expr3>

If your expressions are uncomplicated statements, then using the ternary expression provides a nice way to simplify your code a bit. Once the conditions get a little complex, it’s often better to rely on the standard if statement.

The elif Keyword

The elif statement looks and functions like the if statement, with two major differences:

- Using

elifis only valid after anifstatement or anotherelif. - You can use as many

elifstatements as you need.

In other programming languages, elif is either else if (two separate words) or elseif (both words mashed together). When you see elif in Python, think else if:

if <expr1>:

<statements>

elif <expr2>:

<statements>

elif <expr3>:

<statements>

Python doesn’t have a switch statement. One way to get the same functionality that other programming languages provide with switch statements is by using if and elif. For other ways of reproducing the switch statement in Python, check out Emulating switch/case Statements in Python.

The else Keyword

The else statement, in conjunction with the Python keywords if and elif, denotes a block of code that should be executed only if the other conditional blocks, if and elif, are all falsy:

if <expr>:

<statements>

else:

<statements>

Notice that the else statement doesn’t take a conditional expression. Knowledge of the elif and else keywords and their proper usage is critical for Python programmers. Together with if, they make up some of the most frequently used components in any Python program.

Iteration Keywords: for, while, break, continue, else

Looping and iteration are hugely important programming concepts. Several Python keywords are used to create and work with loops. These, like the Python keywords used for conditionals above, will be used and seen in just about every Python program you come across. Understanding them and their proper usage will help you improve as a Python programmer.

The for Keyword

The most common loop in Python is the for loop. It’s constructed by combining the Python keywords for and in explained earlier. The basic syntax for a for loop is as follows:

for <element> in <container>:

<statements>

A common example is looping over the numbers one through five and printing them to the screen:

>>> for num in range(1, 6):

... print(num)

...

1

2

3

4

5

In other programming languages, the syntax for a for loop will look a little different. You’ll often need to specify the variable, the condition for continuing, and the way to increment that variable (for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++)).

In Python, the for loop is like a for-each loop in other programming languages. Given the object to iterate over, it assigns the value of each iteration to the variable:

>>> people = ["Kevin", "Creed", "Jim"]

>>> for person in people:

... print(f"{person} was in The Office.")

...

Kevin was in The Office.

Creed was in The Office.

Jim was in The Office.

In this example, you start with the list (container) of people’s names. The for loop starts with the for keyword at the beginning of the line, followed by the variable to assign each element of the list to, then the in keyword, and finally the container (people).

Python’s for loop is another major ingredient in any Python program. To learn more about for loops, check out Python “for” Loops (Definite Iteration).

The while Keyword

Python’s while loop uses the keyword while and works like a while loop in other programming languages. As long as the condition that follows the while keyword is truthy, the block following the while statement will continue to be executed over and over again:

while <expr>:

<statements>

Note: For the infinite loop example below, be prepared to use Ctrl+C to stop the process if you decide to try it on your own machine.

The easiest way to specify an infinite loop in Python is to use the while keyword with an expression that is always truthy:

>>> while True:

... print("working...")

...

For more examples of infinite loops in action, check out Socket Programming in Python (Guide). To learn more about while loops, check out Python “while” Loops (Indefinite Iteration).

The break Keyword

If you need to exit a loop early, then you can use the break keyword. This keyword will work in both for and while loops:

for <element> in <container>:

if <expr>:

break

An example of using the break keyword would be if you were summing the integers in a list of numbers and wanted to quit when the total went above a given value:

>>> nums = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10]

>>> total_sum = 0

>>> for num in nums:

... total_sum += num

... if total_sum > 10:

... break

...

>>> total_sum

15

Both the Python keywords break and continue can be useful tools when working with loops. For a deeper discussion of their uses, check out Python “while” Loops (Indefinite Iteration). If you’d like to explore another use case for the break keyword, then you can learn how to emulate do-while loops in Python.

The continue Keyword

Python also has a continue keyword for when you want to skip to the next loop iteration. Like in most other programming languages, the continue keyword allows you to stop executing the current loop iteration and move on to the next iteration:

for <element> in <container>:

if <expr>:

continue

The continue keyword also works in while loops. If the continue keyword is reached in a loop, then the current iteration is stopped, and the next iteration of the loop is started.

The else Keyword Used With Loops

In addition to using the else keyword with conditional if statements, you can also use it as part of a loop. When used with a loop, the else keyword specifies code that should be run if the loop exits normally, meaning break was not called to exit the loop early.

The syntax for using else with a for loop looks like the following:

for <element> in <container>:

<statements>

else:

<statements>

This is very similar to using else with an if statement. Using else with a while loop looks similar:

while <expr>:

<statements>

else:

<statements>

The Python standard documentation has a section on using break and else with a for loop that you should really check out. It uses a great example to illustrate the usefulness of the else block.

The task it shows is looping over the numbers two through nine to find the prime numbers. One way you could do this is with a standard for loop with a flag variable:

>>> for n in range(2, 10):

... prime = True

... for x in range(2, n):

... if n % x == 0:

... prime = False

... print(f"{n} is not prime")

... break

... if prime:

... print(f"{n} is prime!")

...

2 is prime!

3 is prime!

4 is not prime

5 is prime!

6 is not prime

7 is prime!

8 is not prime

9 is not prime

You can use the prime flag to indicate how the loop was exited. If it exited normally, then the prime flag stays True. If it exited with break, then the prime flag will be set to False. Once outside the inner for loop, you can check the flag to determine if prime is True and, if so, print that the number is prime.

The else block provides more straightforward syntax. If you find yourself having to set a flag in a loop, then consider the next example as a way to potentially simplify your code:

>>> for n in range(2, 10):

... for x in range(2, n):

... if n % x == 0:

... print(f"{n} is not prime")

... break

... else:

... print(f"{n} is prime!")

...

2 is prime!

3 is prime!

4 is not prime

5 is prime!

6 is not prime

7 is prime!

8 is not prime

9 is not prime

The only thing that you need to do to use the else block in this example is to remove the prime flag and replace the final if statement with the else block. This ends up producing the same result as the example before, only with clearer code.

Sometimes using an else keyword with a loop can seem a little strange, but once you understand that it allows you to avoid using flags in your loops, it can be a powerful tool.

Structure Keywords: def, class, with, as, pass, lambda

In order to define functions and classes or use context managers, you’ll need to use one of the Python keywords in this section. They’re an essential part of the Python language, and understanding when to use them will help you become a better Python programmer.

The def Keyword

Python’s keyword def is used to define a function or method of a class. This is equivalent to function in JavaScript and PHP. The basic syntax for defining a function with def looks like this:

def <function>(<params>):

<body>

Functions and methods can be very helpful structures in any Python program. To learn more about defining them and all their ins and outs, check out Defining Your Own Python Function.

The class Keyword

To define a class in Python, you use the class keyword. The general syntax for defining a class with class is as follows:

class MyClass(<extends>):

<body>

Classes are powerful tools in object-oriented programming, and you should know about them and how to define them. To learn more, check out Object-Oriented Programming (OOP) in Python 3.

The with Keyword

Context managers are a really helpful structure in Python. Each context manager executes specific code before and after the statements you specify. To use one, you use the with keyword:

with <context manager> as <var>:

<statements>

Using with gives you a way to define code to be executed within the context manager’s scope. The most basic example of this is when you’re working with file I/O in Python.

If you wanted to open a file, do something with that file, and then make sure that the file was closed correctly, then you would use a context manager. Consider this example in which names.txt contains a list of names, one per line:

>>> with open("names.txt") as input_file:

... for name in input_file:

... print(name.strip())

...

Jim

Pam

Cece

Philip

The file I/O context manager provided by open() and initiated with the with keyword opens the file for reading, assigns the open file pointer to input_file, then executes whatever code you specify in the with block. Then, after the block is executed, the file pointer closes. Even if your code in the with block raises an exception, the file pointer would still close.

For a great example of using with and context managers, check out Python Timer Functions: Three Ways to Monitor Your Code.

The as Keyword Used With with

If you want access to the results of the expression or context manager passed to with, you’ll need to alias it using as. You may have also seen as used to alias imports and exceptions, and this is no different. The alias is available in the with block:

with <expr> as <alias>:

<statements>

Most of the time, you’ll see these two Python keywords, with and as, used together.

The pass Keyword

Since Python doesn’t have block indicators to specify the end of a block, the pass keyword is used to specify that the block is intentionally left blank. It’s the equivalent of a no-op, or no operation. Here are a few examples of using pass to specify that the block is blank:

def my_function():

pass

class MyClass:

pass

if True:

pass

For more on pass, check out The pass Statement: How to Do Nothing in Python.

The lambda Keyword

The lambda keyword is used to define a function that doesn’t have a name and has only one statement, the results of which are returned. Functions defined with lambda are referred to as lambda functions:

lambda <args>: <statement>

A basic example of a lambda function that computes the argument raised to the power of 10 would look like this:

p10 = lambda x: x**10

This is equivalent to defining a function with def:

def p10(x):

return x**10

One common use for a lambda function is specifying a different behavior for another function. For example, imagine you wanted to sort a list of strings by their integer values. The default behavior of sorted() would sort the strings alphabetically. But with sorted(), you can specify which key the list should be sorted on.

A lambda function provides a nice way to do so:

>>> ids = ["id1", "id2", "id30", "id3", "id20", "id10"]

>>> sorted(ids)

['id1', 'id10', 'id2', 'id20', 'id3', 'id30']

>>> sorted(ids, key=lambda x: int(x[2:]))

['id1', 'id2', 'id3', 'id10', 'id20', 'id30']

This example sorts the list based not on alphabetical order but on the numerical order of the last characters of the strings after converting them to integers. Without lambda, you would have had to define a function, give it a name, and then pass it to sorted(). lambda made this code cleaner.

For comparison, this is what the example above would look like without using lambda:

>>> def sort_by_int(x):

... return int(x[2:])

...

>>> ids = ["id1", "id2", "id30", "id3", "id20", "id10"]

>>> sorted(ids, key=sort_by_int)

['id1', 'id2', 'id3', 'id10', 'id20', 'id30']

This code produces the same result as the lambda example, but you need to define the function before using it.

For a lot more information about lambda, check out How to Use Python Lambda Functions.

Returning Keywords: return, yield

There are two Python keywords used to specify what gets returned from functions or methods: return and yield. Understanding when and where to use return is vital to becoming a better Python programmer. The yield keyword is a more advanced feature of Python, but it can also be a useful tool to understand.

The return Keyword

Python’s return keyword is valid only as part of a function defined with def. When Python encounters this keyword, it will exit the function at that point and return the results of whatever comes after the return keyword:

def <function>():

return <expr>

When given no expression, return will return None by default:

>>> def return_none():

... return

...

>>> return_none()

>>> r = return_none()

>>> print(r)

None

Most of the time, however, you want to return the results of an expression or a specific value:

>>> def plus_1(num):

... return num + 1

...

>>> plus_1(9)

10

>>> r = plus_1(9)

>>> print(r)

10

You can even use the return keyword multiple times in a function. This allows you to have multiple exit points in your function. A classic example of when you would want to have multiple return statements is the following recursive solution to calculating factorial:

def factorial(n):

if n == 1:

return 1

else:

return n * factorial(n - 1)

In the factorial function above, there are two cases in which you would want to return from the function. The first is the base case, when the number is 1, and the second is the regular case, when you want to multiply the current number by the next number’s factorial value.

To learn more about the return keyword, check out Defining Your Own Python Function.

The yield Keyword

Python’s yield keyword is kind of like the return keyword in that it specifies what gets returned from a function. However, when a function has a yield statement, what gets returned is a generator. The generator can then be passed to Python’s built-in next() to get the next value returned from the function.

When you call a function with yield statements, Python executes the function until it reaches the first yield keyword and then returns a generator. These are known as generator functions:

def <function>():

yield <expr>

The most straightforward example of this would be a generator function that returns the same set of values:

>>> def family():

... yield "Pam"

... yield "Jim"

... yield "Cece"

... yield "Philip"

...

>>> names = family()

>>> names

<generator object family at 0x7f47a43577d8>

>>> next(names)

'Pam'

>>> next(names)

'Jim'

>>> next(names)

'Cece'

>>> next(names)

'Philip'

>>> next(names)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

StopIteration

Once the StopIteration exception is raised, the generator is done returning values. In order to go through the names again, you would need to call family() again and get a new generator. Most of the time, a generator function will be called as part of a for loop, which does the next() calls for you.

For much more on the yield keyword and using generators and generator functions, check out How to Use Generators and yield in Python and Python Generators 101.

Import Keywords: import, from, as

For those tools that, unlike Python keywords and built-ins, are not already available to your Python program, you’ll need to import them into your program. There are many useful modules available in Python’s standard library that are only an import away. There are also many other useful libraries and tools available in PyPI that, once you’ve installed them into your environment, you’ll need to import into your programs.

The following are brief descriptions of the three Python keywords used for importing modules into your program. For more information about these keywords, check out Python Modules and Packages – An Introduction and Python import: Advanced Techniques and Tips.

The import Keyword

Python’s import keyword is used to import, or include, a module for use in your Python program. Basic usage syntax looks like this:

import <module>

After that statement runs, the <module> will be available to your program.

For example, if you want to use the Counter class from the collections module in the standard library, then you can use the following code:

>>> import collections

>>> collections.Counter()

Counter()

Importing collections in this way makes the whole collections module, including the Counter class, available to your program. By using the module name, you have access to all the tools available in that module. To get access to Counter, you reference it from the module: collections.Counter.

The from Keyword

The from keyword is used together with import to import something specific from a module:

from <module> import <thing>

This will import whatever <thing> is inside <module> to be used inside your program. These two Python keywords, from and import, are used together.

If you want to use Counter from the collections module in the standard library, then you can import it specifically:

>>> from collections import Counter

>>> Counter()

Counter()

Importing Counter like this makes the Counter class available, but nothing else from the collections module is available. Counter is now available without you having to reference it from the collections module.

The as Keyword

The as keyword is used to alias an imported module or tool. It’s used together with the Python keywords import and from to change the name of the thing being imported:

import <module> as <alias>

from <module> import <thing> as <alias>

For modules that have really long names or a commonly used import alias, as can be helpful in creating the alias.

If you want to import the Counter class from the collections module but name it something different, you can alias it by using as:

>>> from collections import Counter as C

>>> C()

Counter()

Now Counter is available to be used in your program, but it’s referenced by C instead. A more common use of as import aliases is with NumPy or Pandas packages. These are commonly imported with standard aliases:

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

This is a better alternative to just importing everything from a module, and it allows you to shorten the name of the module being imported.

Exception-Handling Keywords: try, except, raise, finally, else, assert

One of the most common aspects of any Python program is the raising and catching of exceptions. Because this is such a fundamental aspect of all Python code, there are several Python keywords available to help make this part of your code clear and concise.

The sections below go over these Python keywords and their basic usage. For a more in-depth tutorial on these keywords, check out Python Exceptions: An Introduction.

The try Keyword

Any exception-handling block begins with Python’s try keyword. This is the same in most other programming languages that have exception handling.

The code in the try block is code that might raise an exception. Several other Python keywords are associated with try and are used to define what should be done if different exceptions are raised or in different situations. These are except, else, and finally:

try:

<statements>

<except|else|finally>:

<statements>

A try block isn’t valid unless it has at least one of the other Python keywords used for exception handling as part of the overall try statement.

If you wanted to calculate and return the miles per gallon of gas (mpg) given the miles driven and the gallons of gas used, then you could write a function like the following:

def mpg(miles, gallons):

return miles / gallons

The first problem you might see is that your code could raise a ZeroDivisionError if the gallons parameter is passed in as 0. The try keyword allows you to modify the code above to handle that situation appropriately:

def mpg(miles, gallons):

try:

mpg = miles / gallons

except ZeroDivisionError:

mpg = None

return mpg

Now if gallons = 0, then mpg() won’t raise an exception and will return None instead. This might be better, or you might decide that you want to raise a different type of exception or handle this situation differently. You’ll see an expanded version of this example below to illustrate the other keywords used for exception handling.

The except Keyword

Python’s except keyword is used with try to define what to do when specific exceptions are raised. You can have one or more except blocks with a single try. The basic usage looks like this:

try:

<statements>

except <exception>:

<statements>

Taking the mpg() example from before, you could also do something specific in the event that someone passes types that won’t work with the / operator. Having defined mpg() in a previous example, now try to call it with strings instead of numbers:

>>> mpg("lots", "many")

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

File "<stdin>", line 3, in mpg

TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for /: 'str' and 'str'

You could revise mpg() and use multiple except blocks to handle this situation, too:

def mpg(miles, gallons):

try:

mpg = miles / gallons

except ZeroDivisionError:

mpg = None

except TypeError as ex:

print("you need to provide numbers")

raise ex

return mpg

Here, you modify mpg() to raise the TypeError exception only after you’ve printed a helpful reminder to the screen.

Notice that the except keyword can also be used in conjunction with the as keyword. This has the same effect as the other uses of as, giving the raised exception an alias so you can work with it in the except block.

Even though it’s syntactically allowed, try not to use except statements as implicit catchalls. It’s better practice to always explicitly catch something, even if it’s just Exception:

try:

1 / 0

except: # Don't do this

pass

try:

1 / 0

except Exception: # This is better

pass

try:

1 / 0

except ZeroDivisionError: # This is best

pass

If you really do want to catch a broad range of exceptions, then specify the parent Exception. This is more explicitly a catchall, and it won’t also catch exceptions you probably don’t want to catch, like RuntimeError or KeyboardInterrupt.

The raise Keyword

The raise keyword raises an exception. If you find you need to raise an exception, then you can use raise followed by the exception to be raised:

raise <exception>

You used raise previously, in the mpg() example. When you catch the TypeError, you re-raise the exception after printing a message to the screen.

For more on raise, check out Python’s raise: Effectively Raising Exceptions in Your Code.

The finally Keyword

Python’s finally keyword is helpful for specifying code that should be run no matter what happens in the try, except, or else blocks. To use finally, use it as part of a try block and specify the statements that should be run no matter what:

try:

<statements>

finally:

<statements>

Using the example from before, it might be helpful to specify that, no matter what happens, you want to know what arguments the function was called with. You could modify mpg() to include a finally block that does just that:

def mpg(miles, gallons):

try:

mpg = miles / gallons

except ZeroDivisionError:

mpg = None

except TypeError as ex:

print("you need to provide numbers")

raise ex

finally:

print(f"mpg({miles}, {gallons})")

return mpg

Now, no matter how mpg() is called or what the result is, you print the arguments supplied by the user:

>>> mpg(10, 1)

mpg(10, 1)

10.0

>>> mpg("lots", "many")

you need to provide numbers

mpg(lots, many)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

File "<stdin>", line 8, in mpg

File "<stdin>", line 3, in mpg

TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for /: 'str' and 'str'

The finally keyword can be a very useful part of your exception-handling code.

The else Keyword Used With try and except

You’ve learned that the else keyword can be used with both the if keyword and loops in Python, but it has one more use. It can be combined with the try and except Python keywords. You can use else in this way only if you also use at least one except block:

try:

<statements>

except <exception>:

<statements>

else:

<statements>

In this context, the code in the else block is executed only if an exception was not raised in the try block. In other words, if the try block executed all the code successfully, then the else block code would be executed.

In the mpg() example, imagine you want to make sure that the mpg result is always returned as a float no matter what number combination is passed in. One of the ways you could do this is to use an else block. If the try block calculation of mpg is successful, then you convert the result to a float in the else block before returning:

def mpg(miles, gallons):

try:

mpg = miles / gallons

except ZeroDivisionError:

mpg = None

except TypeError as ex:

print("you need to provide numbers")

raise ex

else:

mpg = float(mpg) if mpg is not None else mpg

finally:

print(f"mpg({miles}, {gallons})")

return mpg

Now the results of a call to mpg(), if successful, will always be a float.

For more on using the else block as part of a try and except block, check out Python Exceptions: An Introduction.

The assert Keyword

The assert keyword in Python is used to specify an assert statement, or an assertion about an expression. An assert statement will result in a no-op if the expression (<expr>) is truthy, and it will raise an AssertionError if the expression is falsy. To define an assertion, use assert followed by an expression:

assert <expr>

Generally, assert statements will be used to make sure something that needs to be true is. You shouldn’t rely on them, however, as they can be ignored depending on how your Python program is executed.

Asynchronous Programming Keywords: async, await

Asynchronous programming is a complex topic. There are two Python keywords defined to help make asynchronous code more readable and cleaner: async and await.

The sections below introduce the two asynchronous keywords and their basic syntax, but they won’t go into depth on asynchronous programming. To learn more about asynchronous programming, check out Async IO in Python: A Complete Walkthrough and Getting Started With Async Features in Python.

The async Keyword

The async keyword is used with def to define an asynchronous function, or coroutine. The syntax is just like defining a function, with the addition of async at the beginning:

async def <function>(<params>):

<statements>

You can make a function asynchronous by adding the async keyword before the function’s regular definition.

The await Keyword

Python’s await keyword is used in asynchronous functions to specify a point in the function where control is given back to the event loop for other functions to run. You can use it by placing the await keyword in front of a call to any async function:

await <some async function call>

# OR

<var> = await <some async function call>

When using await, you can either call the asynchronous function and ignore the results, or you can store the results in a variable when the function eventually returns.

Variable Handling Keywords: del, global, nonlocal

Three Python keywords are used to work with variables. The del keyword is much more commonly used than the global and nonlocal keywords. But it’s still helpful to know and understand all three keywords so you can identify when and how to use them.

The del Keyword

del is used in Python to unset a variable or name. You can use it on variable names, but a more common use is to remove indexes from a list or dictionary. To unset a variable, use del followed by the variable you want to unset:

del <variable>

Let’s assume you want to clean up a dictionary that you got from an API response by throwing out keys you know you won’t use. You can do so with the del keyword:

>>> del response["headers"]

>>> del response["errors"]

This will remove the "headers" and "errors" keys from the dictionary response.

The global Keyword

If you need to modify a variable that isn’t defined in a function but is defined in the global scope, then you’ll need to use the global keyword. This works by specifying in the function which variables need to be pulled into the function from the global scope:

global <variable>

A basic example is incrementing a global variable with a function call. You can do that with the global keyword:

>>> x = 0

>>> def inc():

... global x

... x += 1

...

>>> inc()

>>> x

1

>>> inc()

>>> x

2

This is generally not considered good practice, but it does have its uses. To learn much more on the global keyword, check out Python Scope & the LEGB Rule: Resolving Names in Your Code.

The nonlocal Keyword

The nonlocal keyword is similar to global in that it allows you to modify variables from a different scope. With global, the scope you’re pulling from is the global scope. With nonlocal, the scope you’re pulling from is the parent scope. The syntax is similar to global:

nonlocal <variable>

This keyword isn’t used very often, but it can be handy at times. For more on scoping and the nonlocal keyword, check out Python Scope & the LEGB Rule: Resolving Names in Your Code.

Deprecated Python Keywords

Sometimes a Python keyword becomes a built-in function. That was the case with both print and exec. These used to be Python keywords in version 2.7, but they’ve since been changed to built-in functions.

The Former print Keyword

When print was a keyword, the syntax to print something to the screen looked like this:

print "Hello, World"

Notice that it looks like a lot of the other keyword statements, with the keyword followed by the arguments.

Now print is no longer a keyword, and printing is accomplished with the built-in print(). To print something to the screen, you now use the following syntax:

print("Hello, World")

For more on printing, check out Your Guide to the Python print() Function.

The Former exec Keyword

In Python 2.7, the exec keyword took Python code as a string and executed it. This was done with the following syntax:

exec "<statements>"

You can get the same behavior in Python 3+, only with the built-in exec(). For example, if you wanted to execute "x = 12 * 7" in your Python code, then you could do the following:

>>> exec("x = 12 * 7")

>>> x == 84

True

For more on exec() and its uses, check out How to Run Your Python Scripts and Python’s exec(): Execute Dynamically Generated Code.

Conclusion

Python keywords are the fundamental building blocks of any Python program. Understanding their proper use is key to improving your skills and knowledge of Python.

Throughout this article, you’ve seen a few things to solidify your understanding Python keywords and to help you write more efficient and readable code.

In this article, you’ve learned:

- The Python keywords in version 3.8 and their basic usage

- Several resources to help deepen your understanding of many of the keywords

- How to use Python’s

keywordmodule to work with keywords in a programmatic way

If you understand most of these keywords and feel comfortable using them, then you might be interested to learn more about Python’s grammar and how the statements that use these keywords are specified and constructed.

Watch Now This tutorial has a related video course created by the Real Python team. Watch it together with the written tutorial to deepen your understanding: Exploring Keywords in Python